IMatch 5, DAM software and Social Science Research

Social science researchers using photography and video as integral parts of their research will soon accumulate very large collections of images, video, audio and text files. Unless you have a system for organizing and cataloguing data, your collection will soon become unmanageable and you’ll not be able to find the photo, video clip or file that you need. There’s not much point having a rare photo collection if you cannot find anything in it. If this sounds like your situation, then you need to take control of your data with a DAM application.

Summary: As you may guess, I’m recommending IMatch 5 as an outstanding DAM application. IMatch is the work of Mario Westphal in Germany who brilliantly and single-handedly created a powerful program that rivals the best that huge corporations can produce. IMatch 5 is relatively easy to use, yet has powerful features beyond the needs of most users, and is regularly updated with new features and bug fixes (there’s few bugs to fix).

Priced at $110 USD, IMatch is not cheap, but nor is it expensive when compared to other DAM software. I’ve been using it for over 6 months now and have used IMatch’s impressive keyword tagging system to catalogue a portion of my collection. If you have a lot of photos, PDF files, MP3s, (and many other types of digital files) and are wondering how to make order out of chaos, then this is really one of the best tools for the job.

Software support for IMatch is amazing too. If you are tired of giant corporation Adobe’s proprietary formats and don’t want to pay their “Creative Cloud” monthly fees forever, then check out IMatch.

Highlights: Professional grade DAM for photos and other digital data. Reliable, fast, efficient. Highly responsive developer who is constantly fixing bugs and updating the program. New features are added in response to user’s requests.

Possible Issues: No complaints, but be prepared to invest time to learn it.

REVIEW

Between 2006 and 2014, I made dozens of research trips to rural areas across north China and took tens of thousands of photos, recorded many hours of video and audio to document nearly every aspect of rural life. Soon my collection became so big, when I needed a particular file for an exhibit, lecture or paper, it became difficult to find. I soon found that my painstakingly acquired digital collection was of little use because I was not able to quickly find a particular file needed for the task at hand.

While commonly used free photo browsing applications can be used for organizing photos, these relatively simple programs have limited capability to apply and manage keywords. And most deal only with photos. I tested out a promising open-source key-wording program known as TagSpace. It proved unusable because it stores keywords by changing the file name to include keywords– a method that introduces more problems than it solves. Clearly, most of the simpler solutions were not going to work for me.

Further searching led to several indispensable tools known as Digital Asset Management (DAM) applications for managing large digital collections. After exploring a number of DAMs, I purchased IMatch 5 and resolved my conundrum of disorganization.

What is Digital Asset Management (DAM) software?

Digital Asset Management (DAM) software provides means for downloading from memory cards, making comparisons for selection and deletion, renaming, rating, grouping, backing up, archiving, and exporting photos and files. There are many types of DAM software that cater to the needs of corporations and individual users. Most deal with a wide range of digital files. For those of you with time on your hands to read a treatise on DAMs, please have a look at David Diamond’s 195 page book “A DAM Survival Guide Management Book”.

Diamond has rather diverse skills– not only is he a DAM specialist, but was one of the early members of the 80s new wave band, Berlin The “DAM Survival Guide” was a bit too much for my needs and instead read articles and reviews to learn about DAMs. Because my primary concern was to organize my out-of-control photo collection, this review focuses on the utility of using a DAM for photo management.

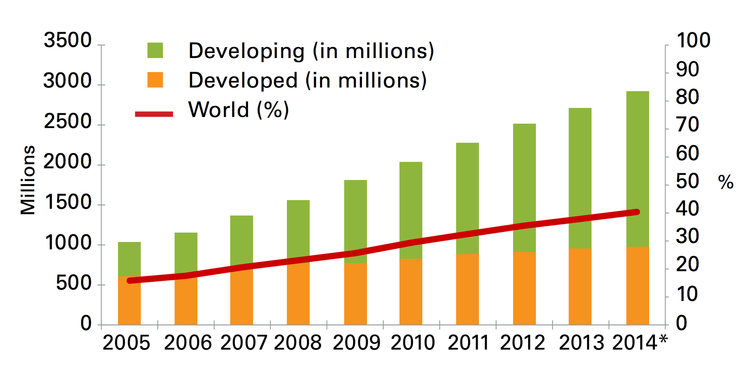

I wanted software that was not cloud-based: I was working in China where the internet to the outside world was blocked 75% of the time, especially in rural areas. Considering a UN report that 60% of the world’s population do not have access to the internet, the trend towards cloud-based software is not something I see as a positive development.

[ “Wall of China” a good photo by Mónidas de Mon. Posted at

“Wall of China” a good photo by Mónidas de Mon. Posted athttps://www.flickr.com/photos/atopeconlatxabaleria/3589639652/in/faves-ownipics/ />

60% of the world’s population without internet access. Source: http://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-60-world-population-3-billion-internet-2014-20140507-story.html />

60% of the world’s population without internet access. Source: http://www.latimes.com/business/technology/la-fi-tn-60-world-population-3-billion-internet-2014-20140507-story.html />

I prefer having my data on my computer, backup up to my own backup device. I wanted a DAM application that would allow me to:

- add keywords to multiple photos at the same time and support the creation of hierarchical keywords

- search and catalogue according to the meta-data that digital cameras embed in photos and allow the addition of new meta-data according to international standards

- use “sidecar” .xml files to hold metadata and have the optional ability to inject the metadata into the RAW files

- create “virtual galleries” of photos. This means that the actual photo files remain in their original place on the hard drive, but virtual copies of the photos can be assigned to different virtual folders

- add captions to photos

- access advanced search capabilities so I can find photos based on various criteria and metadata

Metadata- The Big Debate

Keywords and captions and all other information about photos is stored in “metadata”. This can be a confusing topic and so a basic explanation is helpful.

Metadata is basically descriptor information about photos and can include the camera’s make and model, exposure settings, workflow and archival details including keywords. Metadata is stored in a range of standardized formats including IPTC, EXIF, XMP or ID3. The metadata contained within JPEG, PNG, TIFF, or RAW photos from a digital camera can be read by software applications created by the camera vendors, and by software created by 3rd party vendors including DAM software.

In addition to being stored inside a photo or file itself, metadata can also be stored in “sidecar” files that point to and describe the original photo or file. Sidecar files files have the same name as the file but end with an .XMP extension. There are advantages and disadvantages to both systems.

Advantages of Sidecar files: Sidecar files are small files created by DAM software that contain descriptive metadata stored in .XML format. The sidecars provide metadata descriptors about the RAW, JPEG or TIFF photo/ file, and usually reside in the same folder. Because sidecar files can accommodate a broader range of metadata than can be embedded in RAW, users can add many more useful descriptors to the file/image. Advantages include:

- the sidecar allows the creation of metadata without altering the original RAW file.

- the sidecar metadata can be read by other 3rd party applications if you decide at some point to switch to another DAM product.

- depending on the DAM software used, if your DAM database becomes corrupted, your crucial metadata is still protected. The information about each RAW image and file is safely contained in the sidecars and the database can be rebuilt by simply having adding the photo folders and their sidecars back into the database.

Disadvantages of Sidecar files: folders that have been catalogued by IMatch will include as many small .XML sidecar files in addition to the original RAW images and files that they point to. The addition of many hundreds of extra small files can look somewhat messy and requires careful management. When you want to move a RAW file to a new location, you must be sure to move the corresponding .XML sidecar file or the sidecar and its original file will become disconnected.

Advantages of injecting metadata into RAW: The advantages of injecting user-generated metadata into RAW files is that the RAW files themselves contain the metadata. There are no additional sidecar files created in the folder. Thus, RAW files can be moved at will without worrying about losing its metadata.

Disadvantages of injecting metadata into RAW: Injecting metadata into RAW files is not recommended by many experts. There are two main reasons:

- RAW formats are proprietary secrets of the major camera manufacturers. The only reason third-party software can work with RAW files is because they have reverse-engineered the RAW formats, perhaps not fully knowledgeable about certain aspects of the RAW format assembly. Purists argue that altering RAW files in any way using reverse-engineered software may result in unforeseen damage.

- Also, when moving or renaming RAW files, the user must take care to move or rename the corresponding sidecar files.

For me, the use of sidecar files is essential. I’m not willing to risk damaging my original RAW files. Having clearly established my criteria necessary in a DAM, I began my search.

As with most software, there are both open source or proprietary DAMs. Whenever possible, I try to choose open-source software for several reasons. Firstly, I believe in supporting open standards. Most people in the world cannot afford to purchase proprietary software and thus open-source software removes barriers to learning. Secondly, the efforts exerted by communities of people working together for non-profit goals is something to be applauded and supported in today’s overly profit-oriented world. Thirdly, the use of open source standards prevents our data and associated work from becoming locked into proprietary formats. For example, the Microsoft WORKS documents I created in the late 1990s are now not easily opened on modern software. The potential to lose access to digital data stored in proprietary formats has led increasing numbers of organizations and various levels of governments around the world to switch to open-source alternatives. (Read about this here and here)

For document writing I rely on LibreOffice, vector graphic design is done in Inkscape, basic photo editing in GIMP, newsletter layout in Scribus, project planning in Freemind. But for some tasks, proprietary software remains perhaps the best choice.

My search for DAM software led to this partial list of software packages with varying DAM capabilities. Most of these are geared to the needs of photographers.

ACDSee Pro

BreezeBrowser Pro

Photo Mechanic

Daminion

digiKam

DBGallery

Helicon Photo Safe;

Photo Supreme

IMatch 5

Lunarship Phototheca

Phase One Media Pro

Undoubtedly each of these programs has its strengths and weaknesses. I do not claim to have tried them all, but I did try Daminion, Photomechanic, and Lightroom. Daminion user complaints about bugs scared me off, and while PhotoMechanic was very good, it was not a fully dedicated DAM. I then moved on to Adobe Lightroom 5. During the several months I used it, I liked the fact I could make edits and adjustments to RAW files in Lightroom, add keywords, search my catalogues, and create photo books ready to print. I happily relied on it for several months but made a conscious decision to abandon it despite its power and convenience. Why abandon software that is easy to use, intuitive and convenient? In 2013, Adobe stopped selling perpetual licenses for products in flavor of a monthly license format or “Creative Cloud” that ties users into their proprietary format, an act of corporate greed that led to an unprecedented loss of consumer trust. Adobe had managed to package together the three aspects of software that decidedly drove me away: proprietary formats, monthly use-fees, and cloud based access.

I decided instead to separate my workflow into two main parts and use separate tools:

1. Use a RAW editor to “develop” photos into JPEG or PNG format files for distribution, publication or online use. After much research, I settled on on PhotoNinja by Picturecode. Photoninja is an outstanding RAW editor and will be the subject of another review.

2. Use a DAM to catalogue and search my collections.

Resolved to find an alternative, I tested the only open source contender, the wonderful digiKam. It runs well on Linux, is supported by a huge community of developers and fans, and has advanced keyword and face recognition features. But the Windows version is buggy and not practical to use for huge projects. Also the digiKam project lacks full time support specialists and the last thing you want is to encounter a bug or data loss after you have spent days cataloguing thousands of photos. I had to give up on it but recommend you have a look.

Each person will have different needs and requirements in a DAM and so selecting the right application for your work will require you to do some reading and research.

While reading many photography blogs and forums, I found many positive reviews about IMatch 5 and after a 30 day trial, decided to purchase it. At $110, it represents good value because the developer is constantly adding significant new features and improvements and has a long track record of being reliable, helpful, and responsive to user needs. Indeed when my database had a problem, I sent the 500mb file for analysis and received a response within a very short time-frame. It is service and support like this that makes me partial to supporting small companies that produce outstanding products.

This review will focus on the use of IMatch 5. Because I’m certainly not an expert user of IMatch, I will focus on its basic functions and how it can be an invaluable tool for researchers and photographers.

IMatch 5 is produced by Photools.com, a company established in 1998 by Mario M. Westphal in Germany. IMatch 5 is advertised as being able to handle databases with hundreds of thousands of images. So far, I have about 50,000 images in my database and the application is performing very well indeed. I am planning to use IMatch 5 to manage over 200,000 research and travel photos, a feat that other users on the IMatch forum claim is well within the program’s capabilities.

The Photools website reports that IMatch 5 is used by professional and amateur photographers, photo agencies, librarians, graphic artists, scientists, government and police in over 60 countries.

Getting started with IMatch is relatively easy, but you will still need to invest a fair amount of time to familiarize yourself with its capabilities, screens and tools. Once you understand how it works, using IMatch will seem quite intuitive and you will have a solid grasp of similar DAM photographic tools. Clearly Photools put a lot of time into the design and implementation of this software. The small size of the download (less than 77meg) compared to Lightroom’s nearly 500 megs suggests that IMatch is extremely well-coded. It runs very smoothly on my Thinkpad W520 notebook with corei7 processor, dual SSD drives and 16 gig RAM.

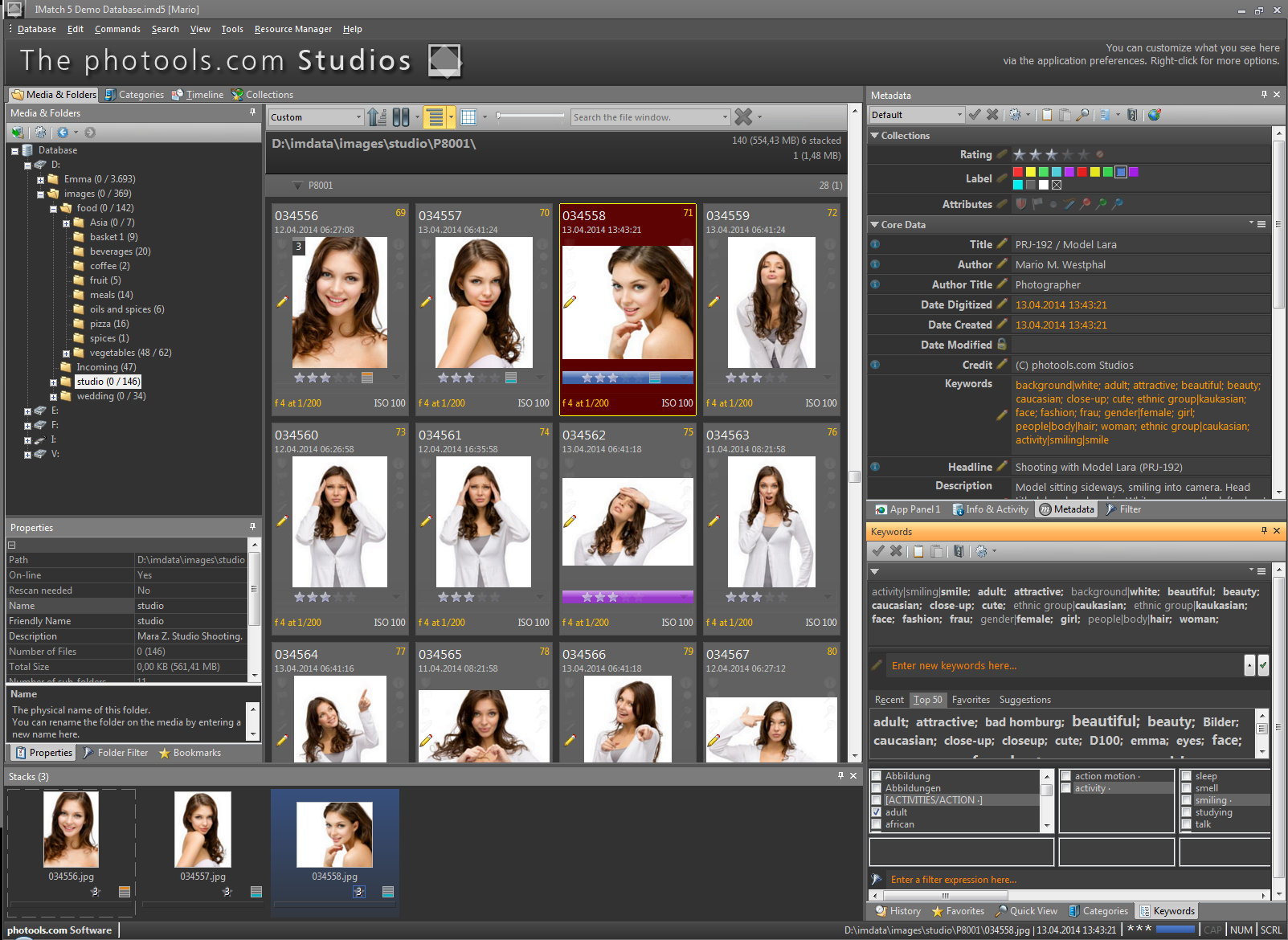

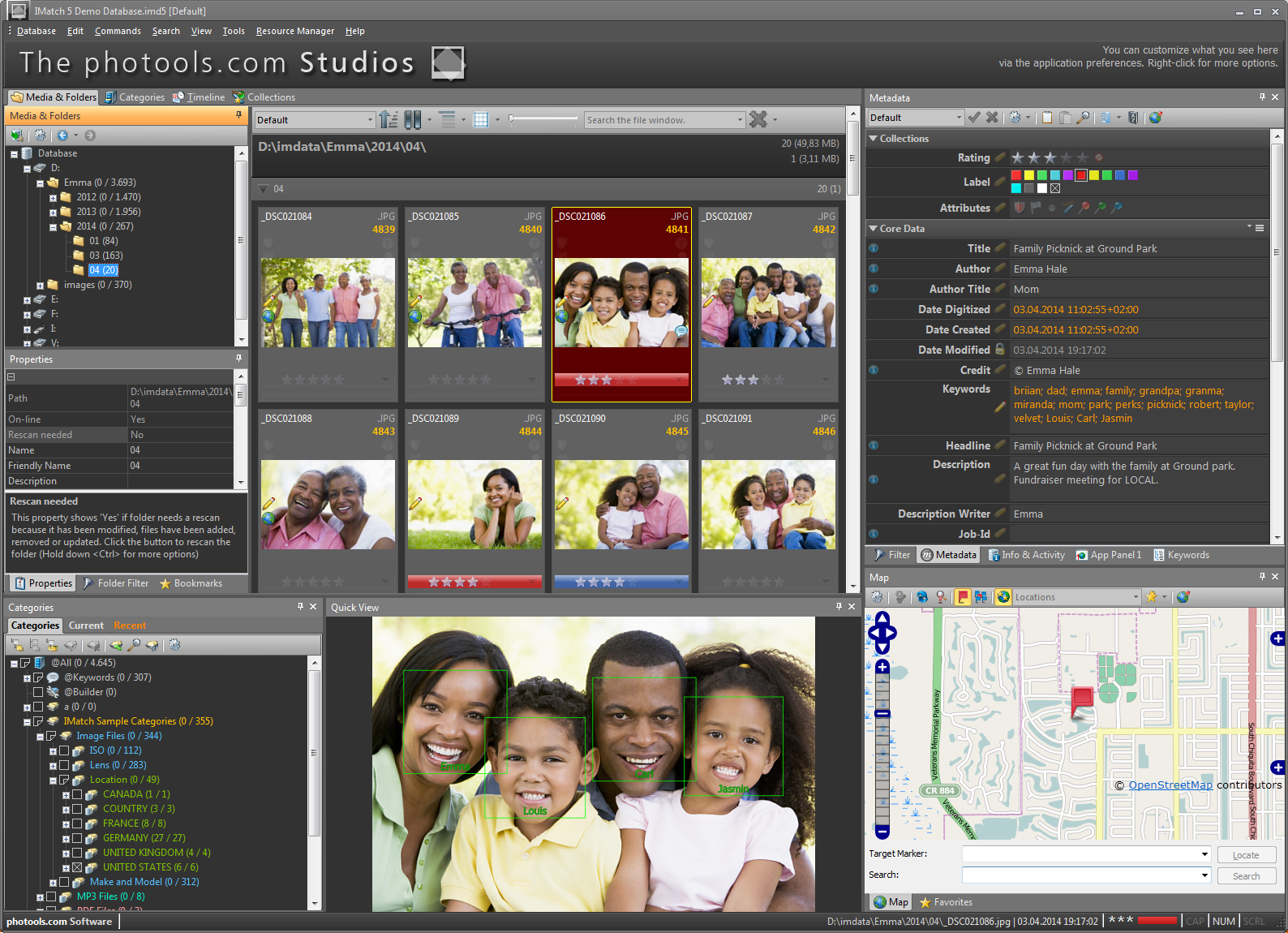

Across the top of the IMatch main screen are 4 main tabs representing different views.

1. Media & Folders View: allows you to work with the physical disks, media and folders that you have included in your database. This view is similar to Windows Explorer, but with a lot of extra functionality.

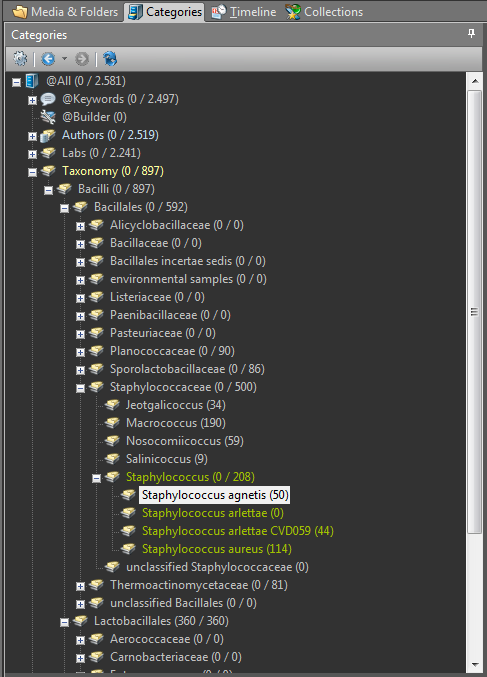

2. Category View: allows you to work with unique IMatch categories and keywords. You can organize file collections in a multitude of ways, including the use of hierarchical key-words.

3. Timeline View: automatically arranges files by EXIF date time-stamp or by similar date values.

4. Collection View: allows you to work with IMatch collections like label, rating, bookmarks, flags, dots and pins. IMatch automatically maintains collections based on when a file was added, modified and viewed, and based on Annotations contained in the file, version states and more.

Each of these Views allows you to look at your file collection in different ways depending on the stage of your workflow. The IMatch 5 manual outlines the main features of the program. They are:

Categories

They allow you to organize, group and cluster your files in very flexible ways, without moving or duplicating the physical files on disk.

Files can be categorized by criteria like the country, place, geographic terrain, season and people, and by social science concepts such as activity, social organization, class, status, religion, and ritual. Each file can be assigned to an unlimited number of categories. You can also create “data-driven” categories in which IMatch categorizes files based on any combination of the embedded metadata. Thus if you want to group all the photos you took with your Pentax K-7 in July 2008, the program can do it. Likewise, if you want IMatch to place in a category all photos that are tagged with the name of your fieldwork site in 2011, it can do that too.

Metatdata Display and Editing

The metadata panel in IMatch gives the user control over over 10,000 different types of metadata. (Of course there’s no need for the average user to need so many varieties, but IMatch can do it). Here, you can add, edit, merge and remove metadata.

Each user can arrange the metadata panel to display a certain arrangement of metadata, and then save this layout. You could, for example, have a layout for PDF documents, one for MP3 audio interviews, for MP3 music, for NEF RAW files by Nikon, PEF RAW files by Pentax, DOXC WORD documents, ODT LibreOffice documents etc. This feature is invaluable to users who work with many different file formats.

The IMatch Thesaurus feature is a handy feature that enables you to save and recall contents for any metadata. It functions as a “master list” of all your metadata and can store it in a hierarchical format.

Working with Keywords

Keywords, or Tags, are an essential feature for organizing digital media. Adding keywords to all of your photos is time consuming. But once you go through this painstaking process, you will wonder how any researcher or photographer could overlook the utility and efficiency of such a system. You will able to nearly instantly find photos (or files) according to keywords such as someone’s name, place, building, animal present in the photo, by landscape attribute or whichever keywords you have applied to your photos.

Universal Thesaurus

This is a distinguishing feature of IMatch that allows the user to maintain a hierarchical vocabulary or taxonomy for keywords and any of the other metadata fields supported by IMatch. This type of hierarchical (or non-hierarchical) list of keywords is sometimes referred to as a “controlled vocabulary”. I’ll talk more about this later.

The Universal Thesaurus is used to build keyword hierarchies (vocabularies) that can be implemented in the Keyword panel.

Controlled Vocabulary and Theory Building

A controlled vocabulary refer to standardized lists of keywords so that keywording is done in consistent and logical fashion. Controlled vocabulary lists can be hierarchical categories or “flat” lists that have no hierarchical organization at all. There are advantages to both but I have found flat lists to be unwieldy. As researchers, our quest is to understand social phenomena and do to do, we must categorize, analyst and interpret the vast range of information that we collect. Systematically surveying our data and grouping it into categories can help with this process.

The process of creating a controlled vocabulary for assigning keywords to photos is tremendously productive aspect of research and should not be looked upon as a bothersome waste of time. Why? Because the process of creating the keyword list is a mental exercise that begins with a very grounded examination of the photo themselves, and progresses to analysis of hidden or latent information, and moves from there to the construction of broader categories and theory.

- enhances our familiarity with our data (photos, videos and other media) leading to improved “groundedness”.

- encourages us to move from a basic understanding of the raw data to perceiving conspicuous and latent themes and categories contained within the data. The meaningful and descriptive keywords that we select for our photo function to underpin broader categories or themes.

- helps us to theorize by making more abstracted interconnections among the patterns, themes and see higher level categories or theorize on broader themes that otherwise might have remained invisible.

Photographers have developed numerous keywording or controlled vocabulary schemes, but most of these are geared towards stock photography. I find them lacking in theoretical rigour and largely inapplicable to my needs. My task – the categorization of tens of thousands of photos about sectarian religious rituals, practice, and training arts in rural China– required a solution better-suited to the needs of social science research. Luckily, I found good advice from experts in the use of QDA (Qualitative Data Analysis) software who explained 2 primary approaches to coding data:

- a priori codes- are derived from outside the data as preexisting ideas or theories, perhaps related to our original research questions.

- grounded codes- emerge from the data when we strive to put aside presuppositions and a priori assumptions and strive to allow themes to appear within the data.

An instructive discussion about the coding process and its benefits can be found here.

Realizing there was no way around it, I spent many days adding keywords to my photo collections in IMatch. And indeed during this process, I began to notice new and fascinating themes and patterns buried within my collection. These gave rise to new categories and caused me to reorganize my hierarchical tree of keywords. Luckily, owing to IMatch’s intelligent design, when you move keywords from one hierarchical grouping to another (for example the keyword “festivals” from a parent keyword “religious rites” to the more appropriate “Social science” parent) the program will change the metadata in all photos coded with “festivals” to ensure that it now includes the parent keyword “social science” rather than “religious rites”. Brilliant.

If you need a controlled vocabulary for use in IMatch or another similar DAM product, there are several good commercial word lists available for sale. Owing to the rather high cost of commercial word-lists, I chose to go with an open-source controlled vocabulary and modified it for social science research. I used the excellent Lightroom Keyword List Project by George Koklas available here. Perhaps at some future point, when my modified list has been fine-tuned to the include keywords applicable to social science research in general, I’ll also release an open-source version. For me, beginning with an open-source word list was an excellent choice.

Renaming Files

Needless to say, the batch-renaming tool in IMatch is extremely helpful. I have just begun to explore its capabilities. Previously, I relied mainly on Metamorphose, an open source file renaming tool (http://file-folder-ren.sourceforge.net/) which is excellent, but has not seen an update in several years.

There are many different methods that photographers use for renaming files. For me, I rely on a simple method that suites my requirements; I move photos into folders named by year, month and day and then rename the photos by year, month and day. For example, photos from my trip to Wanshou Temple are placed into a folder entitled “2014_05_May_01 Wanshou Temple”. This ensures that the Windows file system will arrange all of the 2014 folders in alphabetical and numerical order. I place the number of the month (“05” for May) in front of the month, otherwise Windows cannot sort the months properly. Then, I use IMatch to batch-rename all of the photos in the folder using the year, month, and day in front of the original file name ie) 2014-05-01_00000.MTS

This way, if I use this photo in another location, I can instantly ascertain when it was taken and where it can be found in my collection. Also, this method precludes the possibility that my collection contains another photo with the same name. This can easily happen if you allow your camera to rename photos according to its built-in counter ie) _000103.MTS will be a number used again by your camera after 9,999 shots (at least with Nikon cameras).

After some experimentation and help from the forum at photools.com, I figured out how to get Renamer move photos on my harddrive into folders named in YYYY-MM-DD format according to the date the photo was taken. It can also add YYYY-MM-DD in front of the original file name. The Renamer can even simultaneously create a backup copy of the original file on another disk. I plan on using this feature to ensure that IMatch places a copy on my main drive and onto my backup drive at the same time. This will prevent catastrophic problems like the one I just faced in 2014 when my 8TB RAID crashed.

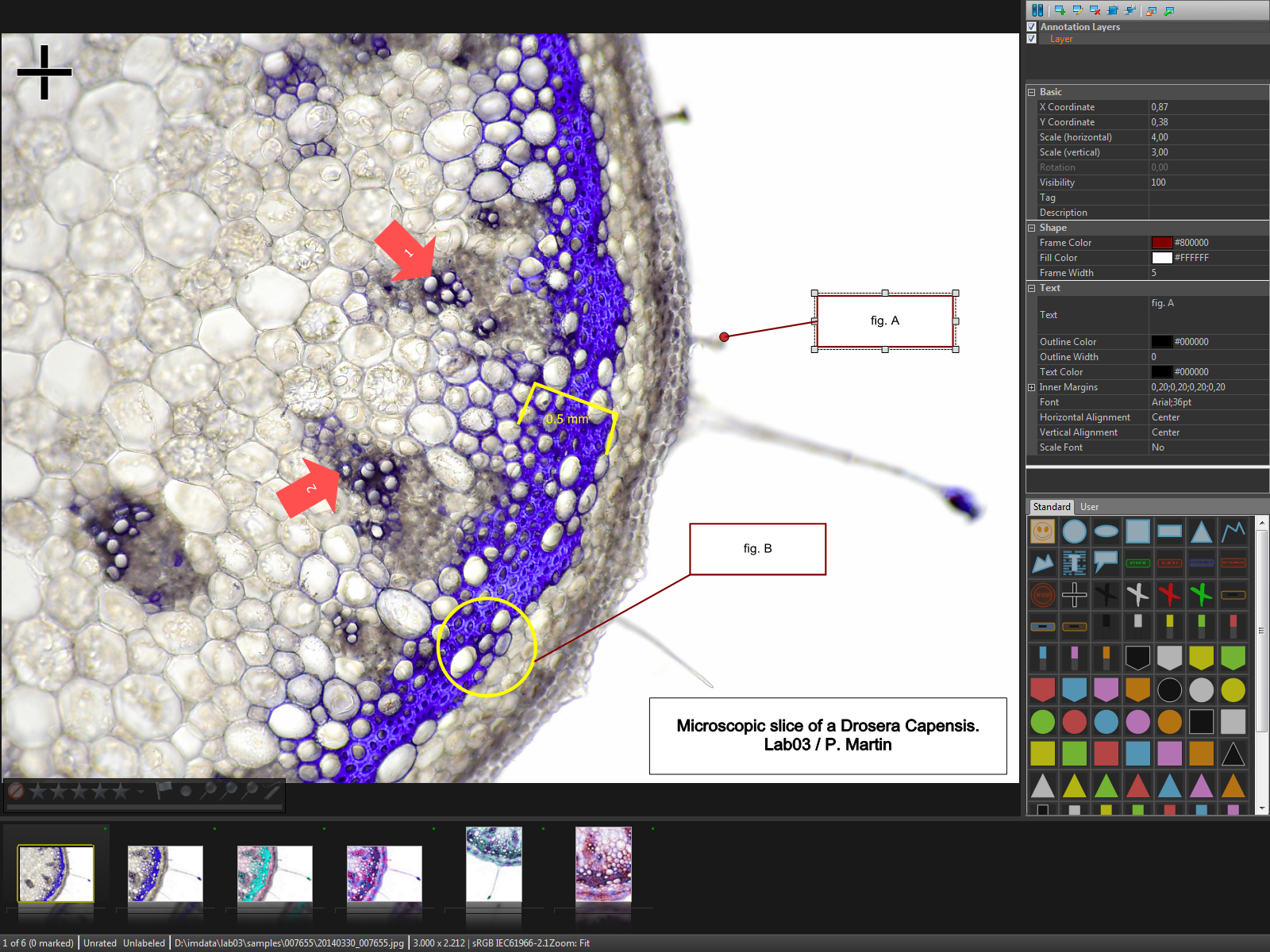

Photo Annotations

For social science researchers, the photo annotation feature is invaluable: it allows the user to make searchable notes in the form of text or drawings on top of photos.

Many of my research photos contain rich ethnographic data that can support descriptive written texts and video in other projects. For example, a photo of an outdoor religious ritual may contain a rare sectarian scripture sitting on a table, to the left and right of which are unusual incense pots dedicated to specific deities. The audience attending the ritual may include familiar and unfamiliar faces. With the annotation tool, you can draw a circle around the scripture, add keywords, and related text. Similarly, you can add keywords to indicate which deities are represented by each incense pot. You can add name-tags to identify familiar faces. This feature is really very useful when analyzing one’s photos and coming up with appropriate keyword schemes. If I am working on a documentary film and need to show a closeup of a particular incense pot, having the photo annotation on the photo will allow me to find it easily.

The annotations that you can draw on top of images are vector-based objects. Because they are not written onto the image, they are entirely non-destructive. These annotations can be text boxes, callouts, various geometrical shapes, polylines, stamps, arrows and flags among others. These vector annotations they can be scaled without loss in image quality. This means that when you zoom in on a photo, the vector annotations will adapt automatically.

The annotations can be displayed in the Viewer, in the Slide Show, and in the Quick View panels. If you want to export an image to JPEG that shows your annotations, this can be done easily using the Batch Processor. Of course, annotations can also be turned off for viewing and export.

Face Annotation

IMatch currently does not have face recognition capability. Including this type of feature in software is apparently very challenging. The developer of IMatch provided some illuminating discussion on this topic in the IMatch user form. Quite unsurprisingly, huge data corporations with deep pockets bought out independent vendors of face recognition software and then took out countless patents to stymie other developers. They did so because the large databases they accumulate of people’s faces, addresses and personal information can be sold to other companies for very high prices. See the enlightening discussion about the creepiness of corporate face recognition technology here by IMatch founder Mario Westphal.

Clearly, Mario is very much concerned about the security of user’s photo data. If he implements facial recognition at some time in the future, we can rest assured that IMatch will ensure that the facial recognition tags remain within IMatch on your computer, and never uploaded to some nebulous cloud server.

Currently, IMatch has a face annotation feature that automatically can locate where faces are on a photo and ask the user to type in an appropriate name. But the software cannot do this automatically. Users will have to tag each person in a photograph with their name. IMatch stores this information within its database to allow users to quickly call up all images marked with one or more face tags.

There is a work-around however. Users can install Google Picasa then adjust Picasa to store face annotations in the XMP metadata contained within jpegs (only jpegs can be processed). Once set up, run Picasa face recognition on a photo collection. IMatch can then be configured to import the face annotation data and and add them as face annotations. For a tutorial on how to do this, see the IMatch help file (http://www.photools.com/3612/google-picasa-face-tags-imatch/). This is a good work-around. Until Picasa or IMatch can do facial recognition on RAW images, I’m unlikely to go through this extra step.

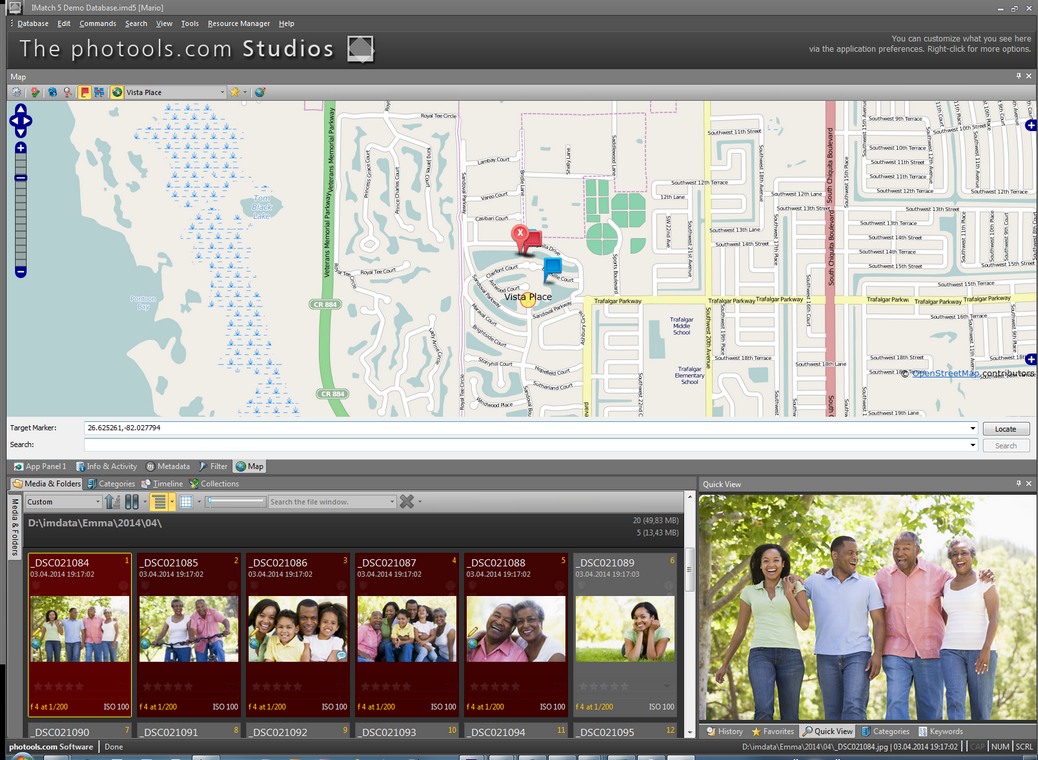

Geo-data and Maps

The Geo-data and Maps feature of IMatch is invaluable to researchers as well. In the Map Panel, users can:

- View your files on the map based on their GPS coordinates

- Add GPS coordinates to your files

- Edit GPS coordinates already contained in your files

- Create and use IMatch Locations to geo-code and reverse geo-code files.

Let’s examine each of these capabilities.

Displaying files on a map

Many digital cameras and nearly all smartphone cameras contain GPS chips that embed geographic metadata into the photos themselves. When these photos are imported into a program that can read geo-data, you will be able to see on a map exactly where on the earth’s surface your photo was taken. Numerous computer programs including IMatch, Corel Photopaint x6, Geosetter and Google Earth have this ability, but for editing this data, I rely on IMatch 5.

In IMatch, to display a file on the map, select the photo in the File Window, and be sure the Map Panel is open. The photo’s location will be shown on the map by a red flag icon. If you move the icon to another location, it will change the geo-data for that file.

If you select multiple files that have GPS coordinates, IMatch will display the location of all the photos on the map.

Add GPS Coordinates to a file

While having a camera with built-in GPS that embeds geo-data is ideal, the majority of my photos were taken with cameras that did not have this ability. This is where IMatch’s geo-editing features and “reverse geocoding” capabilities are outstandingly useful.

Between 1992 and 2014, my fieldwork research took me to dozens of villages in Shandong, Henan and Hebei provinces in north China where I shot many thousands of photos while doing research. During field research trips, I wrote detailed notes that I arranged in a database in MaxQDA, a QDA (Qualitative Data Analysis) program. MaxQDA allows the user to code textual data with keywords and search through a database of textual, video and photographic data and display the locations of photos and related data. Using IMatch to geo-tag my photos allows me to quickly find all photos taken in a particular place and include these with fieldnotes and other related data in MaxQDA.

In IMatch, you can add geo-data

- automatically by looking up and assigning geo-data within IMatch

- manually by entering lat-long geo-data locations for each photo

Let’s examine these two methods.

Automatic entry of geo locations

The process of finding an address or location or place for a given set of coordinates is called reverse geo-coding. Manually looking up latitude longitude locations can be time consuming, and franking rather boring. Thankfully, IMatch has the ability to automate this process and liberate researchers from some drudgery.

To find a country, city, town or landmark, you can type in the place name in the Search field below the map in the Map Panel. Be sure to enable GeoNames in the options of Search Service (go to EDIT – PREFERENCES – GEO & MAPS). If you enabling Google-based searches, you can also look up addresses.

Reverse Geocoding: If your photos already have lat-long geo-data associated with a set of photos, IMatch can use Reverse-Geocoding to look up the address or location and embed the locations in the photo metadata. This is very useful if you want to search your database for all photos taken, for example, on College Avenue, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada, or in the vicinity of Kamakura Daibutsu, Japan.

Manual entry of geo locations: In IMatch there are several ways to manually add geo-data to a photo.

- Metadata Panel you can manually enter the latitude and longitude for the currently selected photo(s).

- In the Map Panel, click on Target Marker and enter a pair of valid latitude/longitude coordinates.

- In the Map Panel, drag a target marker to the desired location on the map. Then click the green arrow button in the Map Panel toolbar to copy the target marker coordinates into the GPS metadata of all selected files.

You can find the latitude and longitude locations for most places in the world using:

- LatLong.net

- WorldAtlas

- CalculatorCat. This site also includes a tool that converts decimal latitude/longitude to degrees, minutes, and seconds.

Other Features:

There are several other features that will not discuss in this review:

- Metadata templates

- Versioning

- Scripting

I’ve simply not used IMatch long enough to know how to use these them. If you have need of these features, the IMatch Photools Community forum discussions offer plenty of expert advice: http://community.photoolsweb.com/

Future-Proofed

As mentioned IMatch 5 can store all of the metadata related to files within its internal catalogue and exported to .XML format sidecar files that are readable by many other applications. In addition, IMatch has some very advanced export capabilities that enable users to export seemingly all forms of metadata and user-created annotations and save them in standard formats that other software can read and import. This is a crucial and brilliant feature because it prevents proprietary lock-in of user data. If development on IMatch should halt, or if you want to use another software product, all of the annotations, keywords, ratings etc can be imported and preserved in the new program.

Conclusion:

IMatch 5 is a powerful DAM application for cataloguing and managing large collections of photos, video clips, pdfs, mp3s, docx and many other types of digital data. IMatch 5 is reasonably priced, well supported by a capable and friendly developer, and has a large community of loyal users who regularly offer help and suggestions to newcomers. Bug fixes and updates to the software are frequent and always free of charge.

First and foremost, it provides the following features:

- Metadata– view, sort and search any camera-created metadata associated with a file. Using this system, you can find all photos shot with an Olympus E1 SLR, at slower than 1/15 sec in Canada. In an instant, you’ll find all your slow shutter shots and time exposures.

- Add new keywords to photos. You can create your own controlled vocabulary of hierarchical (or non-hierarchical) keywords to add social science concepts and themes to photos. Simply the process of adding keywords to photos can assist with theory building and understanding the thematic links among images.

- Rename Files– when you import photos from your camera’s memory card, IMatch can sort the photos into folders according to Year, Month and Day or other custom criteria. It can also rename the images in each folder according to your needs.

- geo-data– you can add or edit latitude/longitude locations for photos and view them on a map. In a glance, you can see where your photos were shot – a process that can help researchers develop a better understanding of the spatial linkages among research sites.

Having capabilities that meet or exceed those of more expensive DAMS costing several hundred dollars, IMatch is an indispensable tool for organizing extensive collections of photos. The maker of IMatch is a small company clearly dedicated to user’s interests rather than to corporate profits. I highly recommend it.

You must be logged in to post a comment.