Working in Kazakhstan was an experience that I’m not likely to forget. The long days at college were filled with that required working late into the evening to complete. By the time weekends arrived, I was very pleased when local friends took me out to visit parks, museums, or enjoy an evening of skating. Participating in different events provided some insights into the lives of my students and coworkers.

Though previous trips had been through scenic landscapes in China, I was quite thrilled to be riding horses in Kazakhstan. The organizer of our activity, Aman picked me up and the three of us made our way to the horse stable on the outskirts of the city where we would meet up with two of his friends. Unfamiliar with the location of the horse stable, our car made a few false starts down bumpy roads before we arrived, quite remarkably, at the same time as the other two fellows who were meeting us there.

Prior to arriving at the horse stable, I imagined we would be riding horses through elm and poplar forests alongside the Ural river and onto broad meadows. At the end of a long day, we would relax in a rustic wooden cottage. However, reality often clashes with imagination. The equestrian centre was situated on a narrow strip of land, perhaps one hectare in size located on the edge of a much larger ranch that raised camel and horses. Many decades ago, the land around Atyrau was a natural grassland steppe but likely during the Soviet era, it had been ploughed for agriculture. Our horse riding grounds was to be a fallow wheat field; the surrounding terrain, typical of the Atyrau region, was flat and featureless punctuated by only a few scraggly trees. The horse-rental building, which provided shelter to the operators, riding coaches and served as a place for tired riders to rest, was a low flat wooden structure built of plywood.

While the natural environment was less than pristine, and the architecture not exactly rustic, I took solace in the fact that I was out of the city, with friends, and with horses. Having grown up on the flat prairies of Saskatchewan, I had long ago learnt to appreciate the subtle terrain and flora of the prairies despite having an affinity for mountains, forest and ocean. Drawing on my prairie aesthetic sense, I took notice of the subdued beauty that lay before my eyes, rather than the beauty that I had imagined I might experience. The dry-brown low grasses, wormwood, tamarisk salt cedar, and feather grass surroundings was reminiscent of the Canadian prairies, and soon I was feeling quite at home with the landscape.

My friends switched between Russian and Kazakh language depending on who they were speaking, a necessity that reflects the complexities of the politics of language. I found this code-switching switching to be fascinating and by asking questions and reading about Kazakhstan’s recent history, the sociolinguistic reasons for it soon became clearer. When Kazakhstan gained its independence in 1991, the country sought to revive the Kazakh language as the official state language to discourage the use of Russian which had become the lingua franca. During the Soviet period, the Russian language had become common in Kazakhstan and other countries with Turkic ethnicities for reasons that included the decline of nomadic culture, the implementation of coercive state policies, practices and incentives to speak Russian in order to shape national identities. Throughout the Soviet period, the lure of social mobility associated with speaking Russian caused a decline in the use of Kazakh language among urban dwellers (Bhavna 1996).

My companions, all of whom are students born after the independence of Kazakhstan, grew up in a new political climate that encouraged the use of Kazakh language and the revitalization of traditional cultural practices. When I asked them about language switching between Kazakh and Russian, they explained that people had different linguistic backgrounds depending largely on their parent’s background. Parents who were educated in Russian and spoke mainly Russian, and those who worked in the former Soviet state apparatus tended to send their children to Russian speaking schools. Others elected to have their children attend schools that taught in Kazakh. Yet another situation, some students from rural villages confided to me that they could not speak Russian at all, spoke only Kazakh at home, and were educated in Kazakh-speaking schools. Others told me that despite being of Kazakh heritage, they had attended Russian schools, spoke mainly Russian at home, and had weak fluency in Kazakh and had trouble speaking with their grandparents. Depending on who they were talking to, people switched language as needed, or if they couldn’t speak that language, sometimes remained silent and let their friends do the talking.  When Amaner, Assia and the others concluded their talk with the horseman, they gave me a summary of the conversation. The ranch raised horses and camels for milk and meat. The horseman had raised horses his entire life, was an expert rider, and enjoyed this part of his work that allowed him contact with students and tourists. I have no idea if the small children leading horses and helping with chores were his grandchildren, but clearly these rural children had grown up with horses and had impeccable equestrian skills that were apparent the moment they settled into the saddle. Quite interestingly, the horse as a cultural notion seems to be still very much embedded in the Kazakh psyche. All of the students who came to the stable to ride today told me that they too wished to become skilled riders because it was part of Kazakh national heritage. Assiya felt a particular affinity for the white horse because she had seen it several months prior in March when the horse stable had brought team of horses, including the white horse, to the college to take part in the Kazakh Nauryz New Years celebrations. A traditional bow-maker I met in the city several months prior had begun studying horseback archery as a way to compliment his interest in the revival of Kazakh cultural traditions. And the retelling of legends and stories about horses maintain the cultural appeal of these animals to persist through modern urban life. This became very apparent when one day at work, I mentioned to a co-worker that I was interested in going riding. She immediately affirmed her interest in horses and began relating a story commonly recounted in her family. Her great grandmother was said to be an expert horsewoman and warrior who, just hours after giving birth to one of her children, mounted her horse unaided and rode off to join a battle against a marauding enemy. Clearly, horses are imbedded in the popular imagination.

When Amaner, Assia and the others concluded their talk with the horseman, they gave me a summary of the conversation. The ranch raised horses and camels for milk and meat. The horseman had raised horses his entire life, was an expert rider, and enjoyed this part of his work that allowed him contact with students and tourists. I have no idea if the small children leading horses and helping with chores were his grandchildren, but clearly these rural children had grown up with horses and had impeccable equestrian skills that were apparent the moment they settled into the saddle. Quite interestingly, the horse as a cultural notion seems to be still very much embedded in the Kazakh psyche. All of the students who came to the stable to ride today told me that they too wished to become skilled riders because it was part of Kazakh national heritage. Assiya felt a particular affinity for the white horse because she had seen it several months prior in March when the horse stable had brought team of horses, including the white horse, to the college to take part in the Kazakh Nauryz New Years celebrations. A traditional bow-maker I met in the city several months prior had begun studying horseback archery as a way to compliment his interest in the revival of Kazakh cultural traditions. And the retelling of legends and stories about horses maintain the cultural appeal of these animals to persist through modern urban life. This became very apparent when one day at work, I mentioned to a co-worker that I was interested in going riding. She immediately affirmed her interest in horses and began relating a story commonly recounted in her family. Her great grandmother was said to be an expert horsewoman and warrior who, just hours after giving birth to one of her children, mounted her horse unaided and rode off to join a battle against a marauding enemy. Clearly, horses are imbedded in the popular imagination.

Prior to industrialization, horses played an important role in transportation in Kazakstan as they did in other countries. But in this part of world, horsemanship was arguably even a more essential part of the lives of nomadic peoples who lived on the steppes. Horses carried them to hunt, allowed them to transport their homes and families, and thus played a key role in nomadic life. With the function of much of society centred on horses, the animals and necessary riding skills came to symbolize a person’s social status. Horse meat, milk, and hides were a crucial part of the diet of nomadic people and even today remain an important part of national cuisine. While the rise of modernity and mechanization displaced the practical need for horses and removed them from their original role as a centrepiece of Kazakh culture, nevertheless the revival of interest in horsemanship and archery is indicative of the desire to preserve Kazakh cultural identity which was badly eroded during the period of Soviet control.

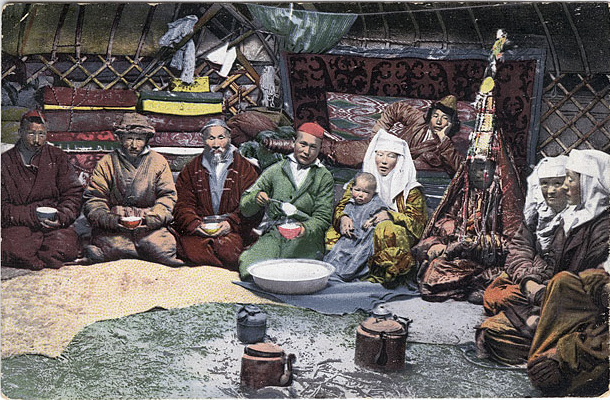

Date: taken between 1911 and 1914

Photo credit: Sergei Ivanovich Borisov [

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ASB_-_Inside_a_Kazakh_yurt.jpg%5B/caption%5D

Once we had gathered inside of the rental shack, our horseman host asked who among us had experience riding and who was a beginner. Beginners should hire a coach, he explained, in order to learn how to ride safely and with skill. Upon hearing this, I was quite excited! The chance to learn from an expert Kazakh horseman was a temptation too great to pass up and I gladly paid the extra 2000 tenge for the privilege of having an expert Kazakh coach. My enthusiasm was comically dampened when my coach strode over to me– he was a 9 year old boy. Earlier, I had admired how this kid and his friends rode expertly around the field before approaching our group on horseback and deftly dismounting. Four horses were led out of the stable. The horseman led a large brown horse over to Assiya first and she was paired with a riding coach who appeared to be in his twenties. Since she was somewhat nervous about riding for the first time, her coach took the reins, began explaining the basics of riding, and and they had set off before we knew it. Two of the other fellows had ridden before and deftly mounted their horses and set off onto the grassy field. [caption id="attachment_2589" align="alignnone" width="1200"] Assiya, riding for the first time, was led off by her coach to begin the afternoon’s ride.

Assiya, riding for the first time, was led off by her coach to begin the afternoon’s ride.

Then it was my turn. The stirrup and saddle were different from what I’d used before. I found the stirrup to be high enough to require considerable effort to mount the horse. Although it wasn’t particularly difficult for me because I’m quite flexible, I wondered how other people manage to get their foot into the stirrup and lift themselves up into the saddle. The difficulty of this most basic manoeuvre made me consider the diverse range of physical strength and skill necessary for horseback riding.

Once I was seated and the horseman was sure I was not about to fall off, he signalled for my coach to join me on the horse. Hardly standing as high as the stirrup, the boy removed my foot from the stirrup, put his foot in, and with a quick heave, lifted himself up onto the horse positioning himself behind me. With a swish of the reigns, we set off slowly into the field.

With my “coach” clearly in charge of our horse, I soon felt a bit discontented simply sitting high and enjoying the ride. I was curious to learn various techniques to control the horse and began asking the tough 9 year old, who could not speak a word of English, what I should do or say to get the horse to turn, to stop or to trot. As expected, the language barrier prevented all communication despite my best efforts that included goofy hand motions and exaggerated facial expressions in trying to ask “How to I get the horse to turn? How can I get her to run?” Though I didn’t learn much about riding from the kid, my other friends were able to translate bits and pieces of what they knew.

Amaner seemed quite comfortable on his horse, though he claimed he had never ridden before.

We made several circular passes around the field getting while I practised how to turn the horse left and right and stop with motions of the reins and the utterance simple Kazakh commands. Each time we passed in front of the horse stable, the horse-keeper stood watching over us to ensure that everyone was in control of their horses and that all was well. As we passed by him, he would call out to the boy and to me. He knew full well that I could not understand him, but yet was also aware that the baritone depth of his voice carried a friendly message. I knew little about horses and their temperament, yet held great affinity towards these noble beasts and hoped to learn more from the older horse-keeper. I had many questions, but each time we circled passed by his sentinel post, there was little time to talk, and my friends who were able to translate were off riding at the far end of the field.

As we rode, I snapped photos trying to capture the mood of the day and the feeling of the landscape. Amaner and the other fellows took my camera to capture photos from their perspective and of the landscape and people as they rode.

Although claiming he had never ridden before, Amaner seemed quite comfortable on his horse and did not require a “coach”. He manoeuvred his horse around the field meeting occasionally with his two friends also rode quite freely, and the three of them picked up useful tips from the riding coaches.

The three Kazakh guys were currently students at various colleges in Atyrau. All three of them had completed other degrees, but unable to find suitable work that paid a decent living wage, and returned to technical college to study programs related to oil technology. Well-educated and international in their outlook, they had good command of English, and were quite interested in learning about horsemanship and traditional Kazakh culture. I found that the three young men and Assiya were all quite interested in Kazakh traditions. In first few years after Kazakhstan became an independent state, there was much concern about how the Kazakh government could build a national identity in light of the long-term effects of Russian settlement in the area and Soviet efforts to marginalize Kazakh culture. A number of academic accounts and novels noted the difficulties in accomplishing this in the 1990s, and how Kazakh people lacked a shared identity. But among the students that my Canadian colleagues and I taught in 2015, this did not seem to be an issue any longer. Many college writing assignments and class assignments discussed local traditions and we teachers were invariably impressed by their replies. Most of them had a strong sense of ethnic identity, and pride in their nation’s history and multi-ethnic composition.

Assiya had begun riding a brown horse, but clearly the white horse caught her eye and she asked one of others to trade with her. One of the strongest students at the college, her command of English was impressive and all of us relied on her as the primary translator. Though she approached horseback riding with some trepidation, she was soon riding confidently and very much attached to her elegant white horse.

As the afternoon drew on and the sun began to set on the horizon, that magical golden afternoon light filled the landscape and accentuated out the beauty of the native grasses and flora. Riding in the fading light, listening to the rustle of grasses, the breathing of the horse and clip-clop rhythm along the worn horse path caused the worries of work, exams, and grading papers to vanish. For a brief time, we were transported into a different world where we experienced the present as it existed – humans, horses, nature and friendship– far from the clamour of modern, profit-oriented competitive society.

By the time the old horse keeper called out to us “Time is up”, the wind had become colder and blew more strongly as we reluctantly made our way back to the plywood rental shack. Though unwilling to see the day come to a close, the four of us were chilled and quite satisfied to take shelter inside the warm building.

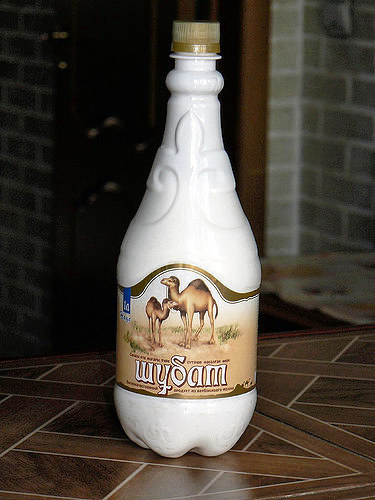

Several women working at the ranch offered us bowls of hot fermented horse milk called kumys and fermented camels’ milk called shubat. This traditional drink made by fermenting camel’s milk with activated kefir, is said to be high in vitamins A, B, and C. Traditional claims that shubat can boost the immune system and can cure ailments of the digestive tract are probably quite valid. Increasing numbers of research studies show that the human gut is host to a vast range of intestinal bacteria that are crucial for good health and that probiotics, in the form of fermented foods, can help prevent and treat allergic diseases (Ozdemir 2010).

Photo credit:

Shubat vs Kumis by Upyernoz on Flickr – 4-Kumis-Shubat on Flickr.

Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Commons – httpscommons.wikimedia.orgwikiFileShubat_vs_Kumis.jpg#mediaFileShubat_vs_Kumis.jpg

Since the fermented foods from different parts of the world host different types of bacteria, eating fermented foods other than North American yogourt is probably a very good idea if we want to ensure ingestion of a wide range of health probiotics. Shubat has a strong milk taste but is less fatty than cow’s milk but with higher levels of lactose and protein. After trying it several times, I began to really quite enjoy its fizzy and tangy flavour.

After drinking down bowls of kumys and shubat, my Kazakh friends took me outside to show me the altybakan or six-pole swing, a traditional game. One person stood on each end of a log that was suspended using ropes from a frame consisting of six poles. We simply stood on the log and swung back and forth.

But traditionally, this game was played by gatherings of young men and women of marriageable age. A couple would stand on the altybakan and be pushed by friends on either side. The couple might sing folk songs along those standing alongside. Simpler altybakan gatherings lasted only through the morning while more elaborate altybakan gatherings, hosted by wealthier households, would invite relatives and friends to attend the gathering and a following dastarkhan feast. As we swung on the altybakan, the thrill of rising up high in the air, followed by a precipitous drop and an immediate rise again seemed like a metaphor for the life cycle changes experienced by us all.

After enjoying swinging on the altybakan for a short time, our day at the horse stable drew to a close. The five of us bade farewell to the horseman and the stable staff who asked us to come again soon before the cold of winter arrived in full force. Walking towards the cars, I was unconsciously smiling and glancing at my friends, noticed they were all smiling as well.

Perhaps we were all marvelling over how an activity as simple as riding a horse could help us forget our myriad concerns and invigorate our spirits. Our car pulled onto the road and drove onto the dark highway.

Notes:

Dave, Bhavna, “Politics of language revival: National identity and state building in Kazakhstan” (1996). Political Science – Dissertations. Paper 85.

http://surface.syr.edu/psc_etd/85

Ö Özdemir. Various effects of different probiotic strains in allergic disorders: an update from laboratory and clinical data. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010 June; 160(3): 295–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04109.x

PMCID: PMC2883099. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2883099/

Entertainment, national games, Kazakh culture and national traditions. Oriental Express Central Asia Website. http://www.kazakhstan.orexca.com/kazakhstan_culture4.shtml

You must be logged in to post a comment.